A Crying Painter

Text / Ce Jian

Painting is probably the most schizophrenic medium today. It is as conventional as it is controversial, owing the classical art form’s long history, which makes it for some a conformist and outmoded craft – at best a popular product on the art market. Its global commercial success, on the other hand, apparently only reduces painting’s intellectual value and credibility as a contemporary art practice.

One reason for painting’s traditionally outstanding role is its eloquence. It does not only create a second nature in mimesis, but is also able to tell stories through representation and iconographic codes. Apart from literary contents it has a non-verbal expressiveness, an eloquence of form and material which was famously explicated by Greenberg as the essence of painterly abstraction. While the modernist critic opposed literary contents with formal purity, ruling the former out, art history shows that verbal and non-verbal elements equally constitute a good painting, enabling it to tell a story while offering a stimulating visuality. Modernism taught us to see painting as a surface (which painters always knew), but it is always more than a surface (which Greenberg knew) – there is a virtual level in every picture, be it a concrete narrative or an aesthetic experience that transcends its material nature. The surface paradigm is further broken up by concepts and references introduced in titles, producing meaning beyond what is visible. Such interplay between image and word is a constant trait in the works of Yuzheng Cheng.

In his paintings and works on paper, Cheng creates a set-up a scene with carefully arranged figures and objects in certain spatial situations and perspectival viewpoints. They are based on photographs which the painter takes using models or other image material, either creating the scene in one shot or combining different pictures to achieve the desired result.

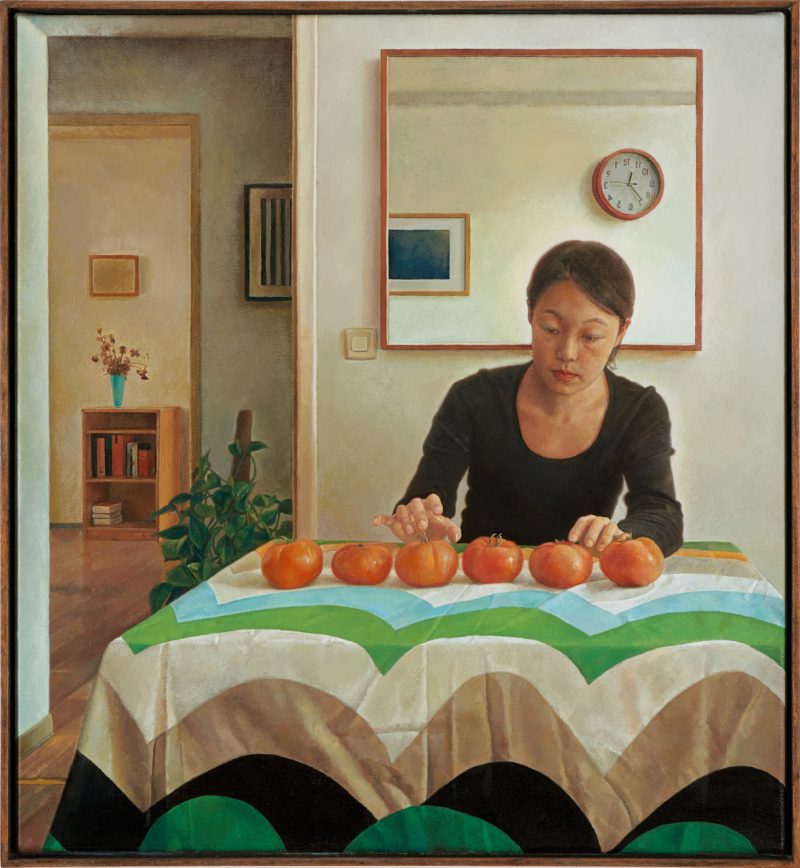

As in Six Big Tomatoes, a model is seated behind a table in a complex interior that leads on to other rooms in the background, thus opening the flat wall parallel to the picture plane. The mirror with a clock reflected in it makes the spatial situation more intricate, breaking up the wall’s surface and echoing the shapes of door and picture frames. While the realist rendering suggests some narrative – typical of salon-sized interior genre scenes – the action of the person slightly touching six tomatoes remains cryptic. For those who are familiar with Chinese art history, the clue might help to recognize an allusion to a famous ink painting of the Southern Song Dynasty, “The Six Persimmons” by the Chan Buddhist monk Mu Xi. Six black-and-white kaki fruits are placed in a row, probably on a table which is no more than a blank space. The fullness of the ink painting that exists as pure potentiality in its monochrome shades and emptiness is matched in Cheng’s work by a complex assemblage of objects, forms and colours, as if turning the spiritual image into a contemporary quotidian scene, a realistic version of the minimalist masterpiece. Still, its reticent character remains – the empty spaces on the wall, the light in the mirror, the self-absorbed figure, all this creates a fiction that is familiar and new at the same time.

A painting is, as Sigmar Polke ironically pointed out in his work The Three Lies of Painting (Die drei Lügen der Malerei) from 1994, always something made-up, a fiction even and especially its attempt to surpass illusion and become real. As long as the painter can acknowledge the medium’s boundaries, he can see the possibilities and freedom of inventing a pictorial reality that is self-contained, without necessarily creating an abstract or surreal imagery. Cheng’s pictures acknowledge that you cannot make a figurative painting without telling a story, but you can decide how much to say and how to put it. You can choose not to be sentimental. You can compose every detail of a scene, give them an elaborate execution. You can widen its meaning by giving clues to art historical references. You can discuss painting within painting.

So it is not surprising that one of the most important models for Cheng is Jan Vermeer’s The Art of Painting (1665-68), an old-master version of Polke’s humorous self-exposure and a brilliant demonstration of painting as a most sophisticated craft. Cheng copied it into his work Studio, corresponding to Vermeer’s alternative title Painter in his Studio. In this work on paper, painting is reduced to a small format and thin layers of acrylic paint, appearing like a faint memory of the lustrous masterpiece. But its lighter, more casual form is rather typical of pictorial commentaries, in this case expressing an idea in a quotation. The original Vermeer shows a compelling illusion of a studio situation, offering the spectator insight into the artist’s laboratory from behind a curtain. This richly coded self-assertion of painting does not only explain the process of its creation, but manifests itself in every painterly detail, climaxing in the microcosm of the tapestry with the map of the Dutch provinces – just as Las Hilanderas (1657-58) by Diego Velázquez is an allegory of painting against the background of another medium, and though its self-assertion is more subtle, it is no less forceful.

Cheng however, puts another frame around Vermeer’s illusion, making it a painting within a painting: The artist in front of the easel that we see from behind is placed again in front of the Vermeer copy, which becomes his finished work. Like repetitive appearances in closed-circuit situations, the figure finds an identical double in ‘his’ own painting. While Vermeer implied a self-portrait, Cheng’s portrait of a painter becomes a portrait of Vermeer creating his masterpiece. Still, the narrative is not about Vermeer – the painter’s figure is a doubled Vermeer quotation, not an imaginary portrait of the historical person. The painter, fusing with the colorful spots into which ‘his’ oil painting was transferred, becomes part of the allegory himself. He came out of the Vermeer picture into the reality of Cheng’s picture, but stepping back another level, we find the real agent behind this virtual one, the old master, that is the only painter present – Cheng himself.

It is by concrete references and narrative clues like these that Cheng reflects painting’s self-referentiality and self-assertion as a historical medium. Thoughts are formulated in painting, not just metaphorical codes, i.e. language. Painting must speak for itself – consequently, every work is emphatically painted, its details and finish are deliberately and decidedly pushed to an extreme, its completion follows a long and laborious working process, from which the painting slowly evolves. The result shows: “It is just a painting”, and yet it says: “The painting is everything”.

Even though the medium’s autonomy has long been claimed by abstraction and no longer has to be proved, the paradigm of the flat surface and its material presence remain a topos for every painter. It is especially hard for representational painting to be convincing without paying tribute to the medium’s self-referential discourse, which necessarily requires a formal and technical consciousness, eventually leading to the question of abstraction. This awareness is a key notion in Cheng’s work, which he considers to be a kind of painting about painting, always keeping in mind that all painting is essentially abstract, considering its material nature, its fictive illusion made of artificial structures.

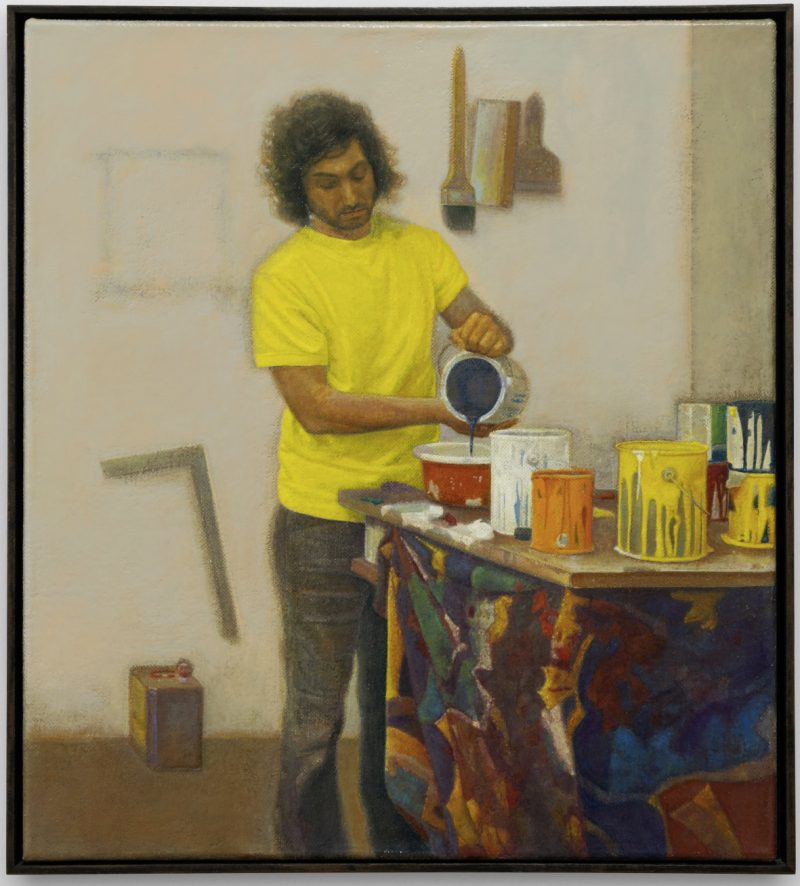

The work An Abstract Painter shows another studio scene, this time a contemporary artist who pours paint into a bowl. The table is full of cans clotted with dried paint, their bright palette is matched by the colourful cloth covering the front, a credit to classical draperies as in Vermeer’s works. Absorbed in his activity, the young painter perfectly mirrors the Milkmaid by Vermeer (ca. 1657-58). Again, the picture is generated using a historical model, but this time Vermeer’s quotidian subject matter has explicitly turned to painting, while the old genre motif is actualized with a present day abstract painter. The symmetry of male/female figure, past/present time, house/studio interior emphasizes the analogy of their work: Both are engaged in an everyday routine, which they do with professional diligence. Cheng’s meticulous realism shows abstract painting in its making, represented by the notorious cans that have become symbols of abstract painting when Jackson Pollock spilled industrial paint on his canvases. Dirty brushes and cans have ever since been requisites of painters’ studios, something Jasper Johns picked up and combined with even more profane objects such as a Savarin coffee can in his sculpture Painted Bronze from 1960.

The style of An Abstract Painter obviously contradicts the common notion of abstract painting, which brings up the general problem of painting’s abstraction – the fundamental question of what makes a painting lies at the heart of this work. Vermeer’s Milkmaid is (as you could say of all his works) as much a genre scene as it is a presentation of painting itself in every visible detail, no matter the object represented. Similarly, the smooth structure of Cheng’s work shows everything in crisp clarity, but at a closer look the brightly coloured parts seem to dissolve into abstract patches and contourless cloudy shapes. The blank wall becomes a diffuse space, while the chromatic kaleidoscope of the tablecloth plays its vibrant counterpart. All material differences are neutralized by a dense all-over texture, made of colour which is nothing more than paint, as the cans overflowing with it literally show.

Pollock, whose painting has changed the idea of the medium significantly, is the subject of Meta Marina Beeck, Art Historian, Accidentally Spilled Wine On The Table While Flipping Through A Jackson Pollock Catalogue. We see a young woman sitting at a table with a glass of wine and an empty bottle, looking down on the blank pages of a book with nothing written on them but the upside-down title Jackson Pollock. Beside her, some red wine is spilled on the table, forming an irregularly splashed pool that stands in peculiar contrast to the geometrical black-and-white patterns of her jacket, as well as the orderly interior full of household items, books and furniture.

The painting has an old-masterly smooth surface made with many layers of oil finish. As in early oil paintings of Jan van Eyck or Rogier van der Weyden, brushstrokes are concealed in the final painting and the handmade nature of the image obscured as well as the process of its creation. Cheng is fascinated by the old masters and their techniques not because of their mimetic virtuosity, as mimesis is no longer a sufficient reason for making a painting, but because of their deep understanding of painting as a form of invention and their knowledge of how to apply its means. It is not nostalgia that draws him to it, but the search for a more fundamental notion of painting: Even though many works by old masters serve to demonstrate their skills, still the picture as such claims a visual objectivityindependent of the painter’s personal sentiment. A characteristic signature style might be present, but it is integrated in the constructive endeavor of the painting, instead of being an end in itself.

On that side, Pollock is a symbolic figure of the individualist, self-expressive Modernist painter. His gestural splashes, no matter how arbitrary, have become icons of a complete realization of physical and emotional expression in accordance with the painting material.

It is that early idea of painting as a personal creation, but not personal self-expression – which Modernism made its primal goal – that Cheng reflects with his quiet, immersed painting method. One could see a self-reflective purism in it, but one that, unlike Modernist abstraction, is not based on subjectivist aesthetics. Cheng tries to use his craft to conceal the matter of technique and simultaneously reveal its constitutive role. He keeps a sober and even attitude in order to focus on painting and its general issues instead of individual style. In this point, he opposes most contemporary (abstract) painting, whose individualism and expressive aesthetics point back to Modernist notions, along with the ineradicable self-image of the heroic (male) painting genius. The dramatic painter that Pollock represented is gone, but the concept of painting as an all-over structure also remains in Cheng’s works – it was not entirely Pollock’s invention anyway.

While Abstract Expressionism marked a vital turn for painting in the 20th century, bringing a boost for the medium, the talk about its end was a constant issue ever since the mid 19th century, when photography appeared as painting’s deadly rival. In his work Seeing The End Of Painting, Cheng refers to this recurring prediction, uttered by historians, critics and artists likewise, with a collage made of printed decorative paper and a small acrylic painting showing a woman in front of a barely visible tripod, who is about to take a picture of a similarly ornamented curtain.

The retro-style print with its playful geometric pattern alludes to Daniel Buren’s red stripes that he worked with after giving up painting in the late 1960s. Next to the designed mass product with its ambivalently decorative and abstract look, is the second mechanical medium posing a threat to painting: photography. Its production process is shown in the picture, whereas its creation – the supposed ‘real’ image – is replaced by the decorative paper on the right side, an industrial product, more abstract, graphic and perfect than any photograph or painting.

It is crucial that the media discourse is carried out in painting, with a dotty blurred rendering that both animates and distorts the depicted objects, giving them a reality and detracting them at the same time. Their intermedia relation is circular: The painted curtain is seen through the imaginary eyes of photography, as indicated by the mathematical grid drawn on it, marking out a distinct image within the painting. But since the mechanical picture only manifests itself in a piece of printed design paper, the question ultimately arises whether any medium can claim a higher level of reality, and thus predominance over others who are considered desolate – does it make sense to talk about the end of painting at all?

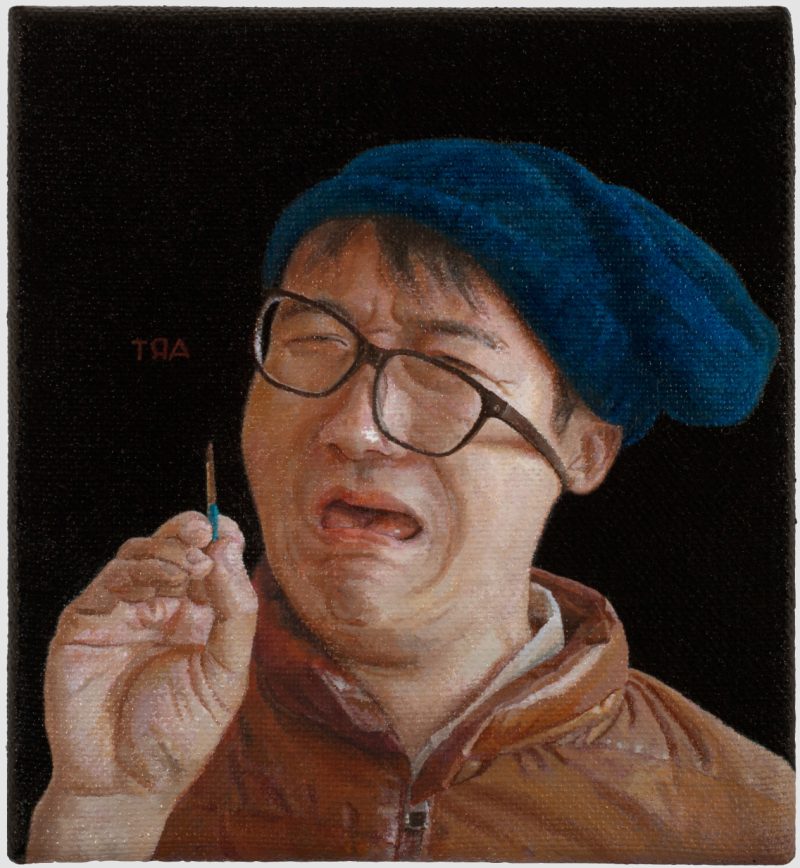

A Crying Painter seems like a victim of this predicament. In this tiny self-portrait, the painter’s face is distorted in a humorously agitated grimace. His cap, a typical painter’s attribute, and glasses are tipped to one side and about to fall off. He has raised a small brush towards the mirror-inverted word “ART” that is written in the air and standing out before the dark background, reminiscent of inscriptions on early oil paintings. Although he appears to have written the letters himself, they hover above his brush like a literal ‘writing on the wall’ – a constant thought and burden.

Cheng’s self-ironical caricature is a modern answer to Jan van Eyck’s Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban, generally assumed to be a self-portrait, in which the painter proudly declares his artistic skill in image and word: “AlC IXH XAN” (“I do as I can”). The dark background and composition in Cheng’s portrait underlines the reference. In an inversion of one of the most famous icons of painter’s portraits – a talking painting at that – Cheng gives a personification of the contemporary plight of the medium that great masters like van Eyck once represented. Shifting the active speech van Eyck accredited to painting to the commenting title A Crying Painter…, Cheng sums up painting’s omnipresent problem in one tragic figure.

The question of painting’s role today poses a challenge in terms of a fatal but undeniable dilemma. Despite its reputation as the commonly best accepted medium, despite its historical significance as the classical art form in which artistic debates and historical movements (also those of 20th century Modernism) took place, painting has to fight for its status among other media now more than ever. It cannot rest upon its historical role, as the meaning of art has expanded severely, its standards and self-understanding are ever changing. So when an artist wants to take painting seriously and make credible works that contribute something relevant and new to art in general – in times when ‘relevance’ is credited mainly to critical, conceptual, politically engaged or interdiciplinary art practices – he or she faces a tricky task.

Historically, painting has always been a complex conglomeration of cultural codes and functions, therefore it was always about something else. But artistically outstanding works also self-reflectively discuss the matter of painting. The title painter’s painter is often attributed to celebrated masters like Titian, Velázquez, Delacroix, Manet or Cézanne, but it means more than a genealogical procession carrying the medium’s heritage: To be a painter’s painter implies an attitude and interest towards the medium, the will to consciously work with painting, finding its possibilities and pushing its boundaries. In painting, the question of what to do is intrinsically tied to the question of how to do it – every concept must come down to a concrete form, every part of the image demands an adequate rendering, no matter which style is chosen.

For this reason, a painter today needs to have a clear notion of painting – just like knowing your instrument, one should know the medium’s principles and techniques, if only to discard them afterwards. Any unconventional style, any ‘bad painting’ will become a kind of know-how and virtuosity in the end anyway, just as all non-art will be absorbed by the art system once it enters it. More than anyone else, a painter needs to know painting’s history, since its present problems can only be understood by knowing its past and its relations to other media. Based on that, one can comprehend the precarious discursive position of painting and develop a convincing artistic practice.

As painting’s crisis seems to have lasted for decades – while we loose grip on it with the expanding spectrum of image media and technologies – a trend reversal is hard to image, there can be no way back. Many artists pride themselves with having ‘given up on painting’ and turned to more ‘contemporary’ media instead, which is a personal alternative, but no artistic solution. For those still willing to try, like Cheng, there is a huge field to explore, as painting is neither isolated nor static, but a facet in the whole system of visual information, concepts and discourses that are continuously moving forward in history. If you can see it as an integral part of contemporary culture and a singular artistic language at the same time, you can try to become a painter’s painter and a contemporary artist in one.