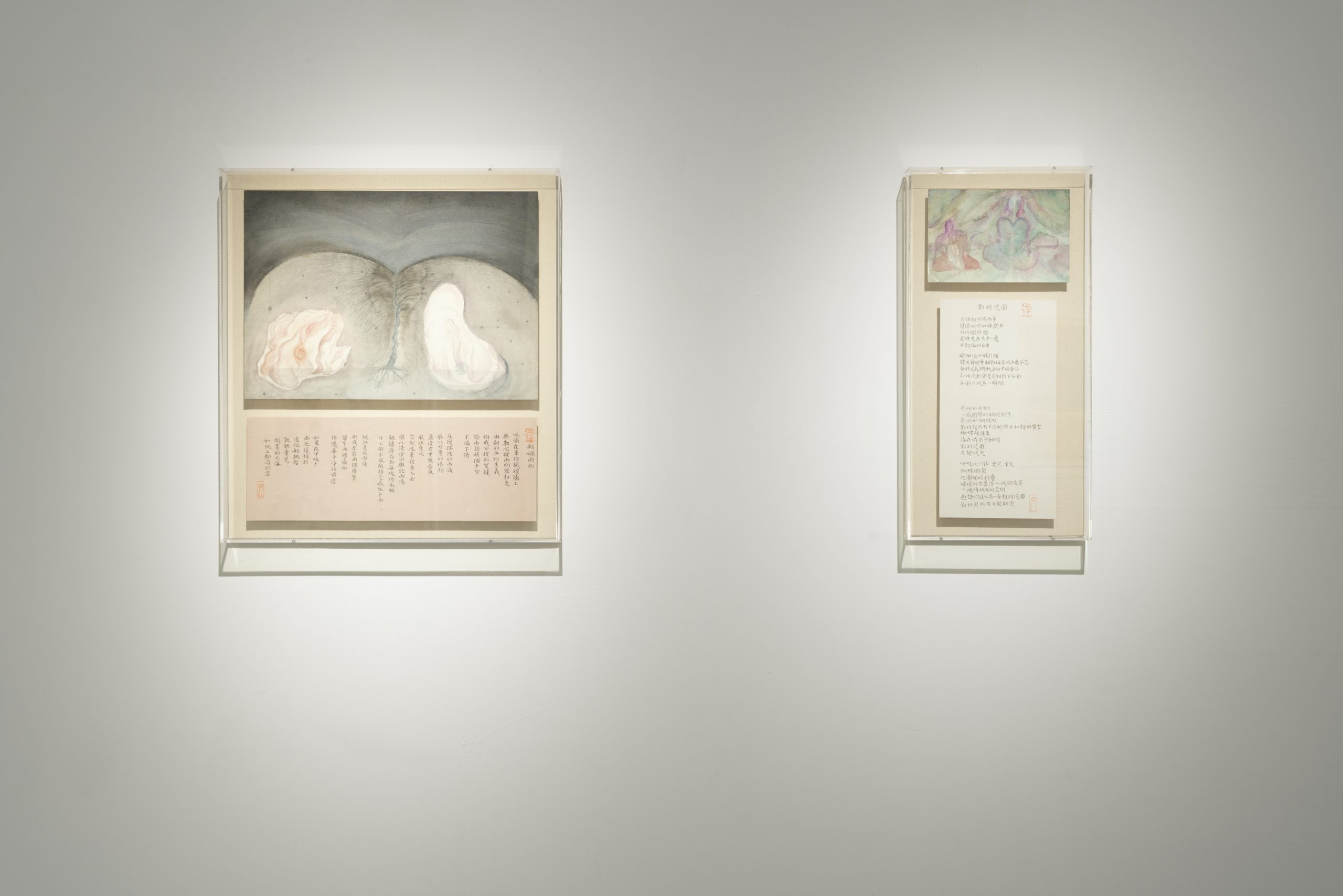

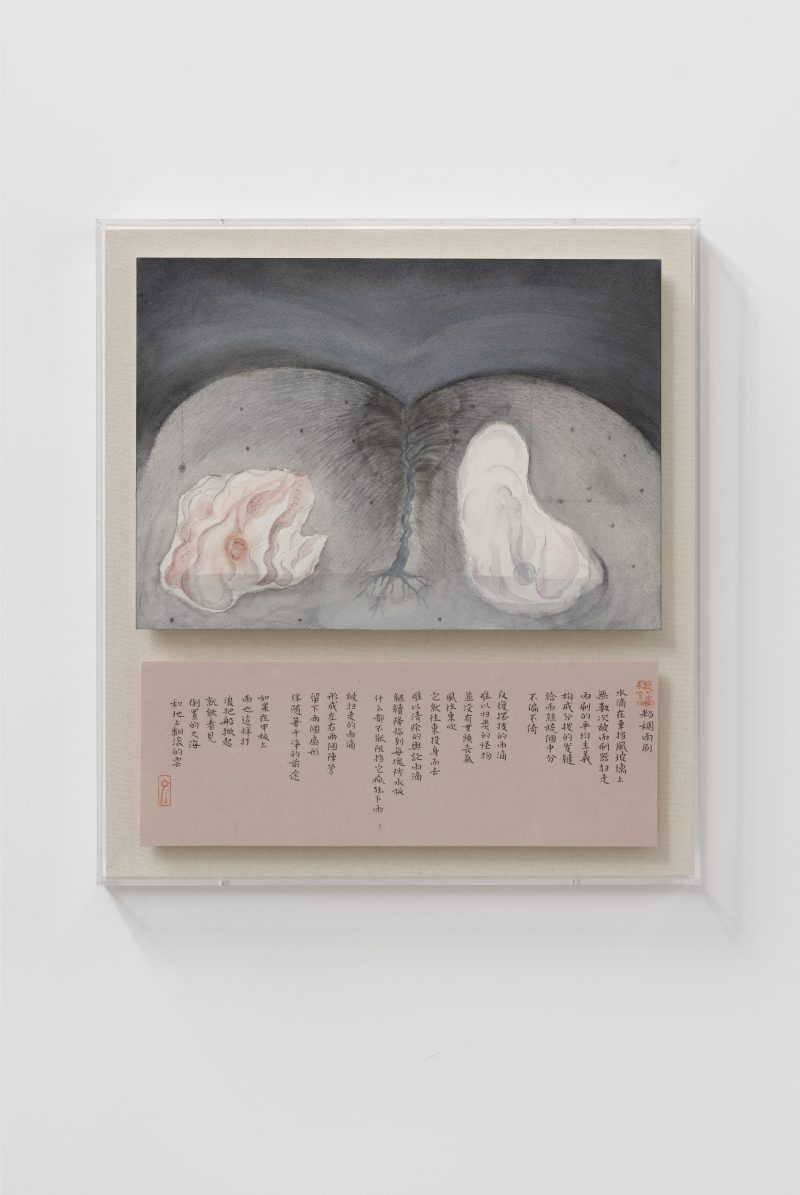

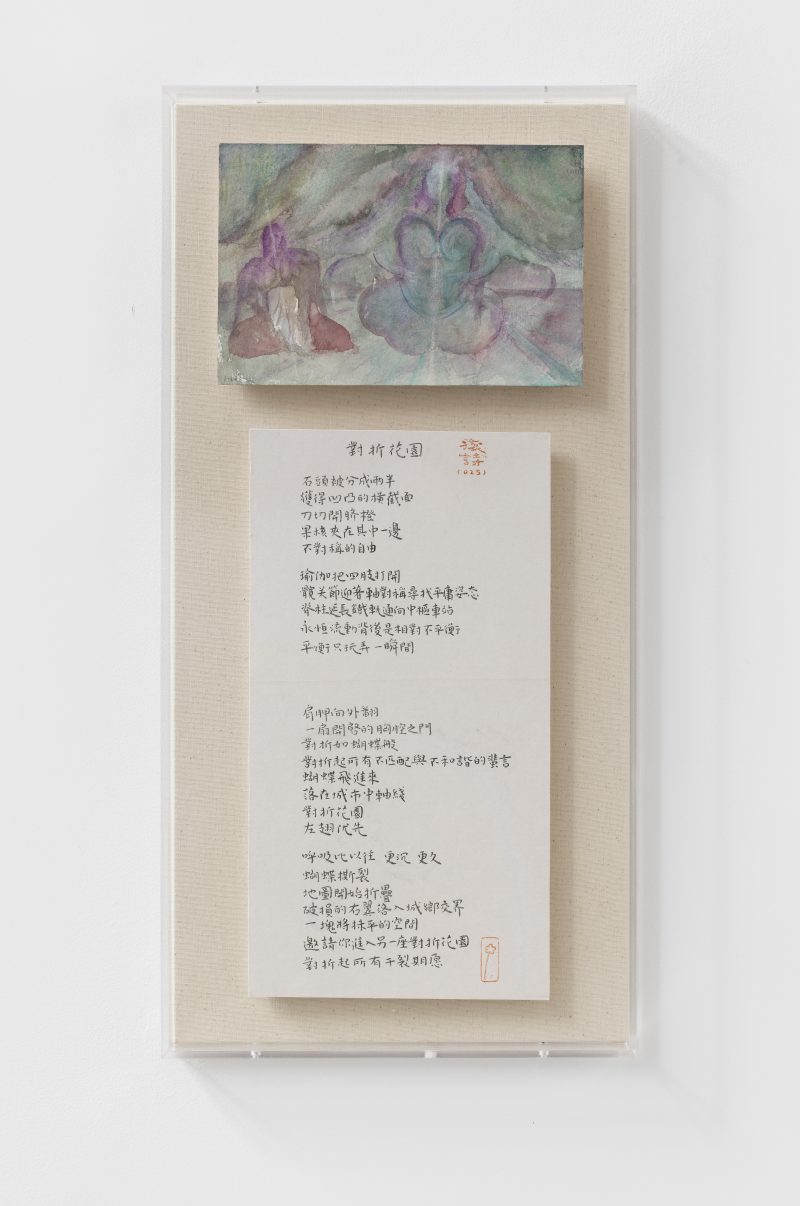

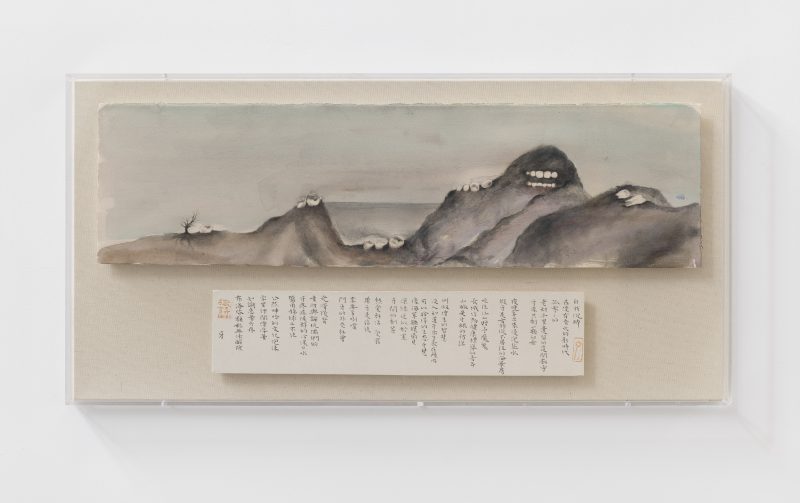

The Destination is Unknown

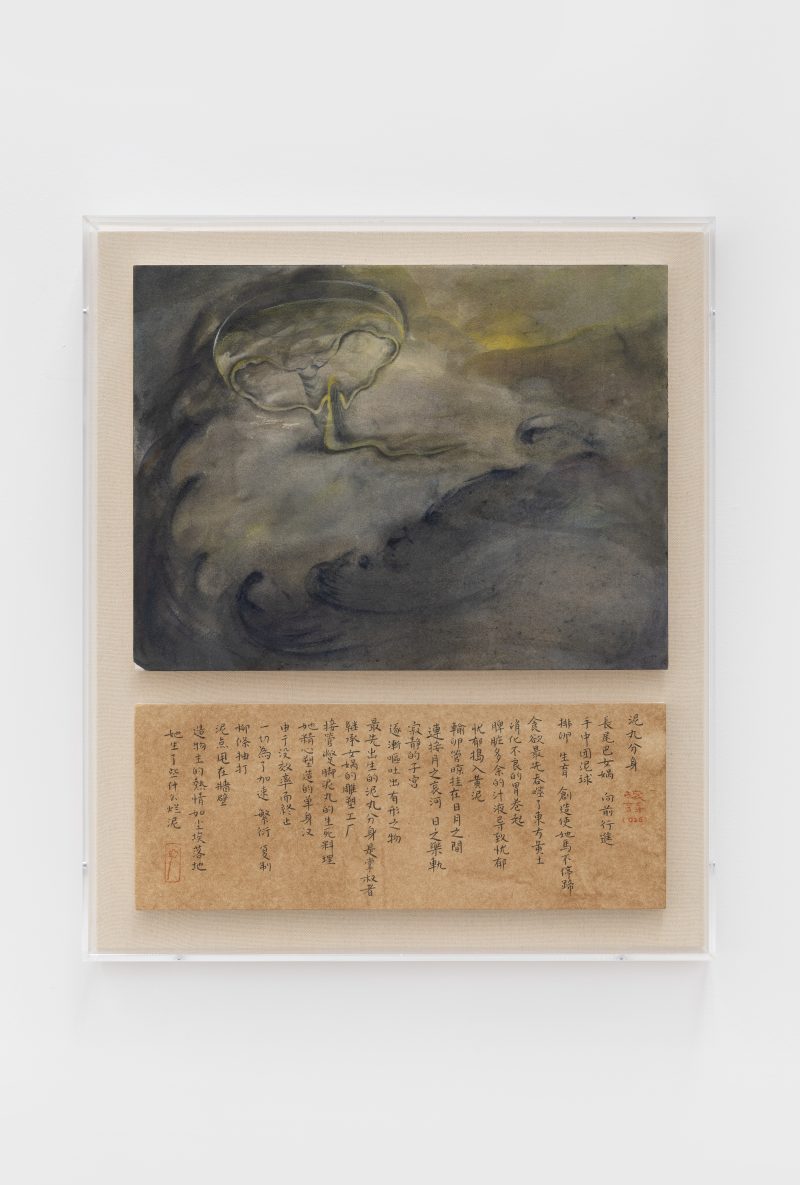

Xie Qun

Curator: Yao Siqing

Group Exhibition, Banri Art Museum, Shantou, Guangdong

Destination unknown. As I typed these words on the computer screen, I, as the curator, suddenly felt a peculiar sense of joy akin to that of a wanderer facing the vast ocean: from Nanjing to the banks of the Pearl River, in different locations across this land, what I sometimes saw was not the present moment, but layers of time, each stage of progress and setback enveloping seeds of unfulfilled ideas; This time, returning home with the eyes of an outsider, while also using the “local culture” framework as a means of escaping the hot topics of the art system, I aim to re-examine the meaning of ‘modernity’ and “globalization” for us. Of course, there is also that overly simplified, supposedly distant “past,” which still triggers our vague aesthetic impulses through visual memory today. Everything remains unclear in theoretical discourse, but the actions guided by these impulses always hold the potential to open up a new dimension of discussion, even if it sometimes feels like a miscommunication of information.

For me, this is already sufficient reason for curatorial practice to take precedence over research-based writing: exhibitions are sometimes visual spaces constructed for reimagination; This is also a sufficient reason for the “destination-unknown” exhibition structure to appear relaxed and diffuse: it attempts to question whether ancient art, as fragments and historical evidence, can establish some new connection with contemporary art, even if they may ultimately present a state of dislocation or even confrontation, and further inquires into what, if any, “whole” of ancient culture might be inheritable. If each new cultural generation has the potential to achieve innovation by “returning” to a certain spiritual resource, then in the face of this so-called gap between ancient and modern times, what can we salvage in the present? How can we update them? What theoretical framework needs to be constructed to free them from their “speechless” state?

At the same time, these questions have a misplaced flip side: within the industry context of what can be called the “art world,” it has its own post-World War II developmental trajectory and a series of events that have been codified as paradigms, such as Duchamp’s “Fountain,” which has become an indispensable part of our contemporary education. Therefore, as we, the latecomers, passively synchronize with the remnants of modernism and the grammatical structures of postmodernism through reform and opening-up, we seem to have no time to ask: in the strictly defined “contemporaneity,” have the mesh of our screening and salvaging become too fine? Can the long cultural history of our homeland only be simplified into the most popular symbolic symbols? Or can it only be placed in a de-subjectivized regional folk area? An even more critical psychological question is: Do we still need to feel regret and guilt for the parts of the past that were not realized? If we shift our perspective to a slightly longer timeframe, such concerns were widely prevalent among the intellectual elite during the late Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China era, leading to endless debates between reformers and moderates. Even someone as erudite and intelligent as Qian Zhongshu still believed that traditional culture as a whole had become a ruin, devoid of vitality, and that all we could salvage from it were bricks and tiles. This was precisely the cultural endeavor he attempted in his work *Guan Zhui Bian*. The “Destination Unknown” exhibition hall is physically located at the Half-Day Art Museum in the coastal city of Shantou, but it also sits at the intersection of the aforementioned issues. The current cultural context has transformed the ambiguous narrative of “Destination Unknown” into a positive state.

Upon entering the exhibition hall, the previous exhibition at the Half-Day Art Museum featured works from its collection, titled “For the Sake of Future Generations: The Collection and Rubbing of Ji Jin.” The museum director, Huang Weijian, also has several years of experience in calligraphy. Interestingly, during our discussions about the exhibition works, I could discern that his visual experience rooted in ancient art has had a significant influence on his temperament and aesthetic preferences. Therefore, if one were to broadly summarize all the participating artists in this group exhibition, it would be that they all possess both experience in studying ancient art and a contemporary artistic consciousness; additionally, the classical aesthetic principle of “appropriate form and function” constitutes the distant horizon behind their visual expressions. In fact, to emphasize this point and to open up the discussion on the relationship between ancient and contemporary art, the exhibition deliberately incorporates Chaozhou wood carvings, Chaozhou embroidery, calligraphy and painting, and other miscellaneous items, allowing them to coexist in the same space. At times, this juxtaposition emphasizes continuity and influence; at others, it highlights a subtle sense of tension. This is left for the viewer’s discernment to uncover, representing another layer of meaning in the “unclear purpose.” Finally, it must be said that maintaining a cautious vigilance against hasty judgments often requires greater courage; “caution in speech” is also a measure derived from the classical world.

In the process of writing this article, I couldn’t help but recall the intellectual adventures of the past few decades: their recklessness and short-sightedness have led to a resurgence of cultural conservatism, with its proponents erecting high walls on the other side. We have come to the seaside, to the edges of other historical clues that have been obscured, to once again feel the creative power of the “unknown destination.” Luan Xueyan, one of the participating artists in this exhibition, created a site-specific installation inspired by Chaozhou embroidery. She said that when she first encountered the style of “embroidery,” she was surprised to discover that it was the same as the fabric given to her by an Italian friend. I believe she received a delayed gift from the maritime civilization of the 18th century.

Installation Views